The gaze of a bison

From North America to Palestine, “the horror of settler colonization has always been a multispecies endeavour”

“We have on this land that which makes life worth living.”

Mahmoud Darwish

Click-clack, click-clack

Hooves on tarmac. A bison saunters by, so close I could extend my arm and let its shaggy fur pass through my fingers. At a bend in the road just ahead, a dozen other bison graze at the forest’s edge, where tall prairie grass meets white spires of golden aspen. Heads down, enveloped by silence, they move unhurriedly, their thickset figures melting into the inky dusk. The temperature is dropping, a chill seeping into the boreal air. A moment so serene it belies the history of this creature and how close we came to losing it.

To hold the gaze of a bison is to feel wonder and warning wash over you all at once.

Bison, in one form or another, have roamed the Earth for over 2.6 million years. The predecessors of modern bison evolved in Eurasia before migrating to North America across the Bering Land Bridge at least 135,000 years ago. While most large mammals, such as saber-tooth cats, mammoths and mastodons, did not survive the late Pleistocene extinction, these hearty creatures did.

At the end of the eighteenth century, perhaps 30 million bison roamed the continent, with most concentrated on the Great Plains, where they flourished in the grassland, prairie and steppe habitats. Encounters with herds of 10,000 and even 100,000 were common into the nineteenth century. In one account, a man described riding in a horse-drawn cart for six consecutive days through masses of bison blanketing the land. Other accounts described unseen herds as sounding like “the booming of a distant ocean” or like “distant thunder”.

Bison were the center of the world to Indigenous nations of the Great Plains. For many of them, bison meat was their single most important food source. From its hide, clothing, blankets and shelter were made. Its bones were chiselled into tools and needles, its horns into cups and spoons. Sinew was wound as thread and bowstrings, while soap was gleaned from its fat. But human-bison relations went far beyond subsistence. Bison were central to kinship systems, political relations and cosmologies of plains Indigenous nations, who considered them sources of guidance, teachers and relatives. As a keystone species, bison were integral to maintaining balance on the prairies, creating the conditions and habitats for other species to thrive, from grouse and burrowing owls to prairie dogs and grasses.

European colonizers, blinded by a worldview that considered humans separate from and above the more-than-human world, the Doctrine of Discovery and racist presumptions of their superiority, had zero regard for bison’s singular centrality to life on the Great Plains. For them, bison were two things: an impediment to white settlement and a commodity resource to serve “the unlimited expansion of colonial capital”.

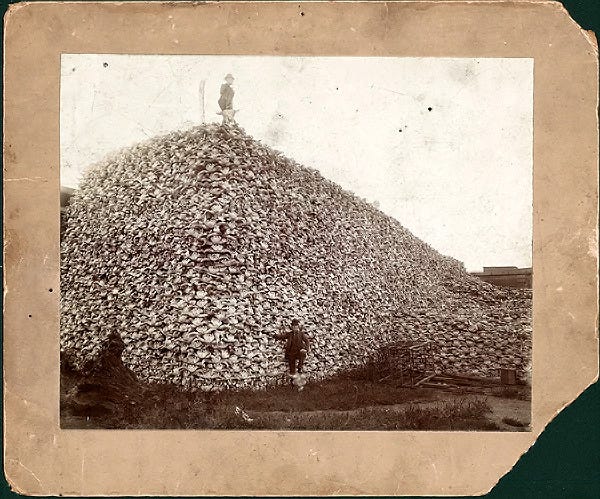

The wide-scale slaughter of bison began in the 1830s, as the colonization of North America increased. White settlers with weapons arrived and demand grew for bison hides and bones, which were rendered as glue and fertilizer, or to produce bone china that was sold across North American and European cities. Most herds were exterminated between 1850 and the late 1870s, and by 1890—within a single human lifetime—settlers had inflicted such ferocious destruction on bison that numbers evaporated, from an ocean to a few drops. Less than 1,000 remained scattered across the continent in small herds, leaving an ecologically arid Great Plains in its wake. A blood-soaked land, emptied and ripe for resettlement.

While the colonizers sought to expand colonial capital through the slaughter of bison, they’d also understood that their extermination, by extension, led to the extermination of Indigenous ways of life. By depleting the land of key species, they’d deplete the people and their culture as well. “Kill every buffalo you can! Every buffalo dead is an Indian gone!” Richard Irving Dodge, a colonel in the US army, told a hunter in 1867[i].

How to destroy a people?

Rip away the centre of their world.

By rupturing Indigenous lifeways and cultures, settler invasion of the prairies destabilized and weakened Indigenous nations, creating the conditions that enabled the colonizers to exert their domination: exacting unfair treaties, forcing Indigenous peoples into reserves and reservation systems and securing control over immense tracts of land. This “violent re-ordering of land and life”—through destroying and claiming what wasn’t theirs—was, as researcher Danielle Taschereau Mamers writes, “the end of a shared world”. One of many colonial harms that the continent and humanity are still reeling from today.

The ancestors of the bison I now watched foraging in Elk Island National Park in the waning light of dusk had barely squeezed through this side of colonization.

At the turn of the twentieth century, the grasslands, aspen parklands, wetlands and lake-studded boreal forest of what would eventually become Elk Island National Park in central Alberta—an area known as Amiskwaciy, the Beaver Hills, to the Cree people—founded to protect one of the region’s last large elk herds, also became a refuge for one of the continent’s last surviving bison herds. Between 1907 and 1912, some 700 bison purchased by the Canadian government were shipped by train from Montana to the park just east of the provincial capital, Edmonton. In the century since, the herd has grown and been used to support conservation efforts in Canada and internationally, with populations translocated to the US and Russia.

You would hope we’d have learned something from all that harm and death, about how to live gentler on this Earth, about how you can’t make your home on top of someone else’s. But to behold the world today is to observe settler colonialism still casting chaos and violence over all forms of life.

Nowhere is this more evident than in Palestine.

Zionists have always loved to tell of how Palestine was “a land without a people for a people without a land”, a reformulation of the colonial trope terra nullius. Settler-colonial states—from the US to Israel—cultivate and depend on such seductive mythology, writes historian and writer Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz. But the land—witness of colonization, the Nakba, military occupation, the steady creep of annexation and ethnic cleansing and, now, the feverish rush of genocide—tells another story. A story of how it wasn’t barren or without people. Of how it’s been a lifeline, always. Of how prior to Zionist colonization, generations of Palestinian farmers cultivated it using methods that respected the limits of the semi-arid climate, growing olives, citrus, wheat and barley, among other crops. Of how to this day, amidst the complexities and indignities engineered by occupation, the fates of hundreds of communities remain tied to olive trees, many of them older than Zionism itself. The story of the land exposes Zionist lies.

Demolish the evidence, rewrite the narrative, fool the world.

Earlier this year, Israeli forces bulldozed a seed bank in Hebron. Seeds, from which Palestinians sow life, sovereignty and steadfastness in the face of occupation and annihilation. Just one of countless violations in a pattern of destruction by the Israeli state and illegal settlers against land—against life— in Palestine. The harms are many. Uprooting, destroying or burning olive and fruit trees (thousands in recent months, beyond the more than three million since 2000). Stealing olives and agricultural equipment for themselves (beyond the land and houses they’ve already stolen). Poisoning or pouring cement into water sources (because what is life without water?). Decimating fields and orchards (because food and agriculture are resistance). Killing and starving livestock (as they do humans). In Gaza, nearly every tree has been cut down, and less than two percent of its cropland can still be cultivated (a famine is never apolitical).

As Taschereau Mamers reminds us, “the…horror of settler colonization has always been a multispecies endeavour.”

How to destroy a people?

Rip away the centre of their world.

Just as European colonization in North America dismantled the means of survival for Indigenous peoples through dispossession and displacement, Israeli assaults on the land are part of systematic efforts to undermine Palestinians’ means of survival by dispossession and displacement. Through the decimation of Palestinian food systems and food sovereignty, depriving Palestinians of access to water and the expropriation of Palestinian land, Israel’s modus operandi from the start has been to weaken Palestinians’ relationship with the land, the foundation of their livelihoods, their culture, their identity—one uprooted olive tree at a time, one confiscated seed at a time, one destroyed crop at a time.

Seventy-seven years of dispossession, fifty-eight years of occupation, two years of genocide. Another patch of Earth depleted by ecological imperialism, another people brutalized, so the colonizers can build new societies in the wastelands of their making. Different century, different targets, different methods, but the objective is the same: erasure.

Though the specificities of colonization are unique to each location, what is consistent about colonialism is that it “has operated and continues to operate through the disruption and re-ordering of relations between humans, land and lively beings,” writes Taschereau Mamers.

Beyond the violence and injustice inherent to all settler colonialism, what makes the Israeli settler-colonial project in Palestine so horrific, so astonishing, so unbearable, is the exploitation and misuse of the Holocaust—one of the greatest crimes against humans the world has known—to advance the Zionist agenda, as political scientist and activist Norman Finkelstein describes in The Holocaust Industry: Reflections on the Exploitation of Jewish Suffering.

This exploitation doesn’t happen in a vacuum. It happens because Western notions of dominance across centuries engender it. It happens because—despite relentless violations of international law, committing atrocity after atrocity against Palestinians and their land, and now, carrying out genocide, the crime of all crimes—Israel remains sheltered by the political, material and moral support of most of the world’s most powerful states, a fact indisputably linked to their own histories as settler-colonial states or other entanglements with empire. It happens because in Zionism, the West sees itself.

As writer and scholar Nasser Abourahme explains:

“Zionism is possibly the most concentrated distillation of colonial racism and state excess in the contemporary world. It’s not just that it’s the inheritor of Europe’s colonial project in its most self-righteous form. It’s also the contemporary vestige of state racism and power in the kind of unrestrained form that elsewhere had to be disavowed. A proud holdover of what everyone else in the West had to pretend not to like anymore. A state racism and power that frees itself from any self-repressive mechanisms, does away with any pretense or even hypocrisy, and wades directly into the unbridled cruelty and sadism that the bourgeois Western political order had to at least pretend it had overcome…It’s in this sense that Zionism is at once both the past and future of the European racial-colonial project.”

Each day, the unceasing horrors of settler colonialism reach new nadirs. In the West Bank, home demolitions peak and multi-species violence swells, intensifying dispossession. In Gaza, scorched earth tactics lay waste to land and starved bodies are corralled like bison to be slaughtered. All this harm and death, so that Israel’s campaign of annexation, ethnic cleansing and resettlement can progress.

Crack

Thud

The colonizer pulls the trigger. A bullet pierces flesh. A body collapses to the Earth.

From the decimated fields of Palestine aching for peace to the emptied plains of North America yearning for the caress of bison hooves, a throughline.

In this world ever undone by colonial violence and domination, spinning and spinning in the maddening gyre, to hold the gaze of a bison is to feel sorrow and to wonder:

What have we done?

Where will we end?

[i] Early settlers erroneously called the animals buffalo, though bison and buffalo are in fact different species.